Share

Ed Vaizey made a splash at Global Counsel’s breakfast “Digital Tech: Bridge or Barrier to Social Mobility?” when he suggested that self-employed platform workers should receive the minimum wage. The former Minister of Culture and the Digital Economy was responding to a succession of controversies over working conditions in the so-called “gig economy”: Deliveroo riders have protested changes in their remuneration structure; the courier service Hermes is potentially facing an investigation from HMRC; and an employment tribunal ruling against Uber could fundamentally transform their self-employed business model.

As Vaizey’s comments show, criticism of the working conditions of online platforms and companies using largely self-employed workforces has moved beyond regular critics in the trade union movement, the Labour Party and left-wing media commentators. Vaizey’s comments will supplement more conventional concerns from centre-right policymakers over the tax contribution of US tech firms and these will play into the independent review led by Matthew Taylor, Chief Executive of the Royal Society of Arts and former adviser to the Blair government, on updating employment policy against the background of the emergence of new business models.

But is the public and media debate on the impact of technology too narrowly focussed on the “gig economy” and the high-profile companies in that sector? Self-employment rates in the UK, while at record levels, have not increased significantly as an overall proportion of employment in the past twenty years. In the same period, there have been major shifts in employment patterns linked to technology and digitisation of functions.

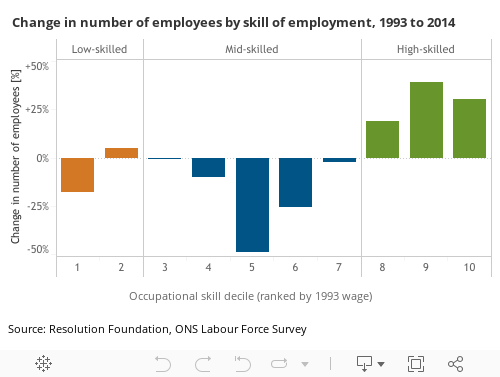

Alan Milburn, Chair of the Social Mobility Commission, has cited Resolution Foundation analysis which demonstrates that there has been a significant loss of employment in middle tier, mid-skilled work in roles such as bank clerks, travel agents, secretarial roles and machine operatives, occupations all vulnerable to digitisation. In contrast, low-skilled jobs have stayed relatively steady while the proportion of high-skilled jobs have increased in the past twenty years. Evidence of major sectoral skills shortages and concerns over the loss of access to EU-wide labour markets post-Brexit demonstrate a misalignment between the industrial requirements of the economy and the skill profile of British workers. For the governing Conservatives, this “hollowing out” of the labour market presents difficult questions over the sustainability of the core centre-right principle of aspiration.

In comparison to these challenges, the role played by new tech platforms can be argued as marginal to the future of the UK’s labour market. However, politics is about symbolism and the controversy over working conditions in the “gig economy” is rapidly becoming a proxy for broader concerns over the structure of the labour market, low pay and reduced social mobility. With the government under Theresa May hinting at a greater appetite for intervention and “good capitalism”, the “gig economy” could find itself in the firing line as ministers look to match rhetoric with action in this area. If even natural supporters such as Vaizey are calling for greater intervention, the “gig economy” may find few political allies in their efforts to resist a new wave of employment enforcement and regulation.

The views expressed in this research can be attributed to the named author(s) only.